by N. T. Wright

One of the greatest journalists of the last generation, Bernard Levin, described how, when he was a small boy, a great celebrity came to visit his school. The headmaster, perhaps wanting to impress, called the young Levin to the platform in front of the whole school. The celebrity, perhaps wanting to be kind, asked the little boy what he’d had for breakfast.

One of the greatest journalists of the last generation, Bernard Levin, described how, when he was a small boy, a great celebrity came to visit his school. The headmaster, perhaps wanting to impress, called the young Levin to the platform in front of the whole school. The celebrity, perhaps wanting to be kind, asked the little boy what he’d had for breakfast.

“Matzobrei,” replied Levin. A typical central European Jewish dish, Matzobrei is made of eggs fried with matzo wafers, brown sugar, and cinnamon. Levin’s immigrant mother had continued to make it even after years of living in London. To him, it was a perfectly ordinary word for a perfectly ordinary meal.

But the celebrity, ignorant of such cuisine, thought he’d misheard. He repeated his question. Levin, now puzzled and anxious, gave the same answer. The celebrity looked concerned and glanced at the headmaster: What is this word he’s saying? The headmaster, adopting a there-there-little-man tone, asked Levin once more what he had had for breakfast. Dismayed, not knowing what he’d done wrong, and wanting to burst into tears, the boy said once more the only answer he could honestly give: “Matzobrei.” After an exchange of incredulous glances on the platform, the terrified little boy was sent back to his place. The incident was never referred to again, but to him it was a horrible ordeal.

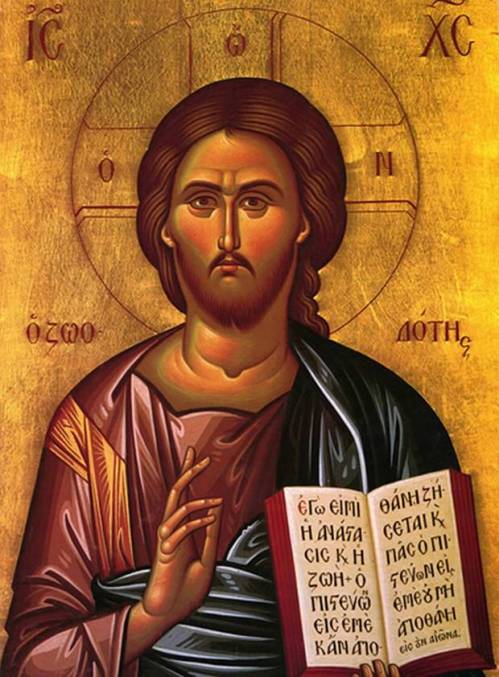

A Jewish word spoken to an uncomprehending world; a child’s word spoken to uncomprehending adults; a word for a food of which others were unaware—it all feels very Johannine. “In the beginning was the Word … and the Word was made flesh” (John 1:1, 14). We are so used to that passage, the great cadences, the solemn but glad message of the Incarnation, that we risk skipping over the incomprehensibility, the oddness, the almost embarrassing strangeness of the Word. “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness didn’t comprehend it; the world was made through him and the world didn’t know him; he came to his own, and his own didn’t receive him” (John 1:5, 10–11).

John is saying two things simultaneously in his prologue (two hundred things, actually, but I’ll concentrate on two): First, that the Incarnation of the eternal Word was the event for which the whole of creation had been waiting all along; second, that creation and even the people God were quite unready for this event. Jew and Gentile alike, upon hearing of this strange Word, cast anxious glances at one another, like the celebrity and the headmaster hearing a little boy telling the truth in a language they didn’t understand.

That is the puzzle of Christmas. John’s prologue is designed to stay in the mind and heart throughout the subsequent story. Never again in the Gospel of John is Jesus referred to as “the Word,” but we are meant to look at each scene—the call of the first disciples, the changing of water into wine, the confrontation with Pilate, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection—and think to ourselves: This is what it looks like when the Word becomes flesh. Or, if you like: Look at this man of flesh and learn to see the living God.

But watch what happens as it all plays out. He comes to his own, and his own don’t receive him. The light shines in the darkness, and though the darkness can’t overcome it, the darkness sure tries. He speaks the truth, the plain and simple words, like the little boy saying what he had for breakfast, and Caiaphas and Pilate, uncomprehending, can’t decide whether he’s mad or wicked or both.

Though Jesus is never again referred to as the Word of God, we find the theme transposed throughout the Gospel with endless variations. The Living Word speaks living words, and the reaction is the same. “This is a hard word,” say his followers when he tells them that he is the bread come down from heaven (John 6:60). “What is this word?” asks the puzzled crowd in Jerusalem (John 7:36). “My word finds no place in you,” says Jesus, “because you can’t hear it” (John 8:37, 43). “The word I spoke will be their judge on the last day,” he insists (John 12:48), as the crowds reject him.