By DAVID CRARY AP National Writer

In a city scarred by broken promises, the Moore brothers, James and Robert, and fellow student Chelsea Inyard are among the lucky ones. The teenagers attend one of Detroit’s most promising new public schools.

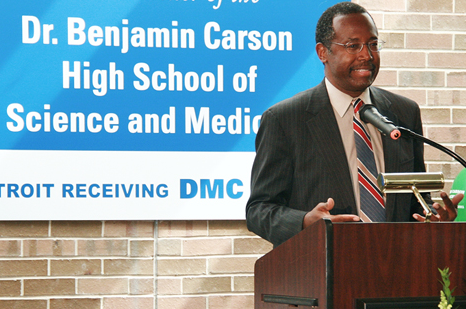

Set in the medical district of the city’s Midtown neighborhood, Dr. Benjamin Carson High School of Science and Medicine, just three years old, offers a rigorous curriculum, gung-ho teachers and gleaming facilities. One recent day, anatomy students studied the Latin terms for parts of the eye; a literature class discussed the psychology of love.

Yet, while the students welcome the opportunities, the challenges of just getting to and from school are a daily reminder that theirs is a city in the throes of the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history, where life places special stresses on young people.

Teachers and parents are fighting to do right by the children, and many believe Detroit is finally on the rise after hitting bottom. Yet they worry about the toll of growing up amid danger, dysfunction and the blight epitomized by tens of thousands of abandoned homes.

“This is what we’re ingraining into kids’ psyches—this emptiness, the lack of safety,” said Tonya Allen, CEO of the Skillman Foundation, which backs many new, child-oriented initiatives. “They’re going into school with a level of fear that something bad is going to happen.”

The landscape includes 88 vacant school buildings that are up for sale—some of the 200 schools closed in recent years due to depopulation. At many schools still open, frequent power outages have created a literal gloom.

High levels of gang violence and premature births combine to make the youth mortality rate the worst of any major U.S. city, according to a recent analysis by the Detroit News.

Even the city’s 300 parks—traditionally a haven for children to play—have mostly become unusable, overgrown wastelands.

“Detroit is a very difficult place to be a child,” said Dan Varner, CEO of an education watchdog group called Excellent Schools Detroit.

Often it’s the grownups rather than kids who worry out loud about Detroit’s woes as formative influences. Many young Detroiters speak hopefully of the future, though the practical obstacles to getting there come up in their conversation, too.

Take, for instance, the Moore brothers, who live on Detroit’s northern boundary, about 10 miles from Ben Carson. Like many high school students, they rely for transport on the city’s crime-ridden, inefficient bus system.

“Some days, I don’t get home until 9 p.m.,” said Robert, a 16-year-old junior aspiring to a military career. He recounted the all-too-common phenomenon of overcrowded buses passing without stopping.

James, who’s 15, says his youth-league football team was sometimes unable to play because field conditions were so bad—”tall grass, nasty bleachers, trash everywhere.”

Like most schools in Detroit, Ben Carson has an overwhelmingly African-American student body. More than 80 percent come from low-income families—not surprising in a city where the child poverty rate of 57 percent is triple the national figure.

“They need our arms wrapped around them,” said the principal, Brenda Belcher. “It’s important to create a culture and climate to support them.”

Sitting patiently in the school’s reception area on a recent day was Michael Inyard, whose daughter, Chelsea, is a 10th grader. Unable to drive because his license is suspended, Inyard rides with her on the bus to and from school.

It’s a brutal schedule, given that he works overnight at a Chrysler plant, but he considers the crowded buses too dangerous for Chelsea to ride alone.

“I’d be a bundle of nerves any other way, wondering what’s going on with her,” the father said.

Speaking generally about Detroit’s upcoming generation, he added, “These kids have a rough time. They’ve got to be on the alert for whatever, whenever.”

———

Ten miles west of Ben Carson, at one of Detroit’s less glamorous high schools, 17-year-old junior Jalen Pickett was indeed on the alert—a police officer was about to shove him during a workshop aimed in part at teaching anger management and conflict resolution skills to a dozen often-in-trouble students.

“How would you react to that?” Officer Melvin Chuney asked the group after using Jalen as his foil.

The setting was a disused classroom on the third floor of Cody High School. The 60-year-old building, in a neighborhood dotted with abandoned brick homes, has deteriorated enough to be the target of a volunteer face-lift effort this summer.

Jalen, now a diligent student with aspirations to be a defense lawyer, had an inauspicious start to high school.

“I got into a fight my first day,” he said. “I was kicked out a lot, didn’t get along with any of my teachers. I cursed on them … I was horrible.”

His penchant for fighting earned him a spot in the new Police Department program—the Children in Trauma Intervention Camp. In essence, it offers the students an alternative to expulsion in the form of training and counseling from police officers and other adult mentors.

“Everybody knows you’re in here because sometimes you made bad decisions,” said the program’s leader, Officer Monica Evans, whose exhortations included biblical references and raw street language.

Tackling the concept of self-reflection, Evans asked the students to write about what limits them.

“I have to be focused and confident that nothing can stop me from getting out of the ‘hood,” said one boy’s statement, read aloud by Evans.

The program has clearly motivated Jalen Pickett. He now opts to wear a necktie each day despite teasing from his friends and is studying hard with hopes of going to an out-of-state university.